Historian Dan Jackson talks about the ideas behind his new book – The Northumbrians: North-East England and its People

Patronised, overlooked, misunderstood, forgotten. A peripheral corner of England well-served by historians but neglected by the rest of the country. Is this the story of North East England? Historian Dan Jackson’s new book The Northumbrians: North-East England and its People acknowledges that while this may be the case, there is much in the region’s past and present to warrant contemporary interest and reflection. This is a book which searches for the deep roots of present realities and argues that the hard-working, heavy drinking, sociable, macho and sentimental North East grew out of centuries of contested border warfare and dangerous, but stimulating, industry.

“We were a great civilisation,” said Jackson when I met him at the Left Luggage Room bar at Monkseaton Metro Station. “But today it’s wrongly seen as a backwater. We have a story to tell. Not enough people know about it.” And yet, maybe it is unsurprising that the region has been so overlooked and neglected in 21st century Britain. “You could say why should the rest of the country pay us any attention? We’re far away. We’re exhausted, knackered. We don’t have the stuff they want anymore. We used to have it but we don’t anymore. Why would anyone be interested in the North East?”

It is the flowering of the region’s two golden ages, that of the Venerable Bede and St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, which kept the flame of Christianity and learning alive in the Dark Ages, and the exceptional inventiveness of the Industrial Revolution, that excites Jackson, and which he believes deserves to be better known. “Those two golden age periods go against the grain of what you might expect from a provincial, peripheral part of England. You’ve just got to look at the list of presidents of the Lit and Phil on the marble plaque at the top of the stairs. It’s an embarrassment of riches, isn’t it? Armstrong, Parsons, Swan, Trevelyan, Stephenson all the greats they’re there. Wow.”

To avoid the pitfalls of using either “Geordie” or “Mackem” and risk inflaming the current Tyne-Wear rivalry, Jackson has chosen the “Northumbrians” as his catch-all term for the people of the region. “I think it’s a more inclusive term. I do think that the whole Mackem thing has just been invented over the past forty years. But we can’t avoid the fact that it has been and people have it as their identity now. I agree that Geordie was used for everyone particularly in the industrial parts of the North East right until the 1980s. But it was widespread, it wasn’t the contentious thing that it is now. And so, to avoid all that, even though Bill Lancaster makes a valiant attempt to try and reclaim it in his Geordies: Roots of Regionalism book, I thought, not only is Northumbrians more inclusive but also allows you to draw out the continuities in a more obvious way. From the Northumbrian world of the Dark Ages through the centuries.”

The “New Northumbrians” were a loose cultural movement on 19th century Tyneside who saw themselves as an alternative, cultured and historic people different from the national norm, and it seems that Jackson, who tweets as @northumbriana, could be their 21st century heir, a new New Northumbrian. “I do have some sympathy with that kind of 19th century generation who stood back and thought, ‘Look at the marvellous things we’re doing in this remote corner of England. Didn’t we keep the flame of Christianity alive in the Dark Ages? Can we find any continuities?’ as I suppose I’m doing in the book. There was a lot of that sort of fanciful stuff in the 19th century which is beguiling and I have no problem with it. But I wouldn’t take it forward into a political agenda necessarily. It’s not like I’m writing a history of Scotland where I’m trying to create a nation here and say, ‘We’ve always had this identity’ and ‘We need our own state.’ I’m not arguing that. I’m saying that the people who lived down the centuries have shared certain attitudes in common. And to explain the way we think and behave.”

***

Dan Jackson grew up in New Hartley, a former pit village in South East Northumberland, in the 1980s. Jackson was part of “that traditional pit village world” but he witnessed merely “the glowing embers of that culture because the pits were more or less shutting or totally shut.” Nevertheless, he had what he describes as “an absolutely idyllic childhood” centred on the “tri-village area” of New Hartley, Seaton Delaval and Seaton Sluice and the neighbouring fields and woods where he played unsupervised. His grandfather was a coalminer who painted in his spare time in his shed. “He wasn’t part of the Ashington group. He was of a later generation but he was one of those real autodidacts, omnivorous in his interests: American westerns, Egyptology, art, politics. I was always struck by the idea that he was a guy who worked with his hands but had this intellectual hinterland which didn’t seem all that typical of what we’ve come to expect from working people.”

It was this experience of close-knit community, hard-work and working class intellectualism that he admires today. But he shakes off any question of looking back at the period with rose-tinted glasses. “I suppose the question might be put, or has been put to me in the past, ‘are you guilty of nostalgia?’ I don’t think you can be nostalgic for a world of poverty and no penicillin or antiseptic, domestic violence and all that stuff. But I certainly admire those generations of people who managed to carve out this world. My grandmother’s catchphrase was always ‘we had nowt but we were happy.’ And I never knew whether she meant that because she grew up in a pit village in the 1920s and ‘30s. Her sister died of diabetes when she was twenty, can you imagine such a thing?”

His father was a city boy who “saw the pit villages as the land that time forgot. He thought the accent was a bit weird to start with as well. He was a Geordie from the West End of Newcastle and he was like, ‘Eh, what are they on about?’ They said stuff like ‘chebble’ for table; they don’t say that anymore.” He worked at IBM as an electrician and had been in the RAF, following his father into the armed forces.

This attraction to the military plays a role in Jackson’s book. “I’ve always had a massively nerdy interest in military history, everything, guns, uniforms, tanks, battleships, a nerdy boy’s interest in it all. I think the profession of arms in the history of the North East is a hugely important golden thread. Certainly, a thread which runs through nearly two thousand years of history. I also think it explains a lot of the Geordie belligerence, the hard lad culture. And it’s been strangely overlooked. The twentieth century military history of North East England is fascinating in its own right but very little has been written about it.”

Since the 1980s and Jackson’s youth, the old pit villages of Northumberland have changed drastically. “It’s very discernible, since I live in the top end of Whitley Bay, you drop, it sounds awful to say, a few socio-economic categories heading north. Parts of Delaval look really shabby. The folk look a bit beaten down, poor. Horrible takeaways, anti-social behaviour. I’m hearing stories from my parents of kids getting beaten up and mugged. There were punch ups in the ‘80s but not people being robbed. Largely those communities were self-policing. There were downsides to that extremely patriarchal world and the close-knit world. But it meant it was self-policing. Surveillance was a big thing.

“Gossip and information were a real currency in those days: ‘What are they up to? Where are they off to? There she goes again. Again! He goes to the club every single night. Can you believe it, every single night? There he goes!’ It was literally twitching net curtains. The surveillance society was a big part of that. As family structures started to change, people came and went a little bit more. People moved and moved, coming in. They weren’t sure where they stood anymore about intervening and having it out with people; knocking on their door and saying, ‘Did yi kna your such and such has been…?’ People are still spying on each other on social media but it used to be a much more physical thing.”

An interest in history encouraged by a teacher called Rob Cunningham, “a bloke from Byker who was inspirational in every sense,” led Jackson to Northumbria University and later Liverpool where he became interested in the history of Irish migration. The book Popular Opposition to Irish Home Rule emerged out of his subsequent doctoral studies back at Northumbria in 2009. But the short-term contracts and geographical mobility required by the historical profession persuaded him to seek a career outside academia. History became a hobby and a bit of fun.

In 2016, Jackson’s blog Northumberlandia caught the attention of the BBC who asked him to appear on an episode of Who Do You Think You Are? “They were looking into Cheryl Tweedy’s past and googling North Shields. I think my blog just happened to come up. They got in touch and said, ‘Would you be interested in doing this programme? You’d have to sign a non-disclosure thing before we tell you who the celebrity is so you won’t go blabbing.’ I said, ‘Yeah fine, whatever.’ And then when they told me I didn’t know who they were talking about. They said, ‘It’s Cheryl.’ I said, ‘Who?’ They said, ‘Cheryl from Girls Aloud.’ And I still wasn’t getting it since she’d changed her name. Again, ‘Cheryl!’ And I said, ‘Oh!’ So, I did a little bit of research. I didn’t have to do much since they provided the material. A lot of people said we had a real onscreen chemistry which I subsequently played up to. She was dead canny, down to earth and interested in what I had to say. She was talking off camera about stuff and said something which I thought was interesting. She said, ‘I love coming back home because nobody begrudges me my success. They’re always pleased to see me and say, ‘Well done Cheryl!’”

This exposure, coupled with Jackson’s growing Twitter presence, led to interest from Michael Dwyer of Hurst Publishers. “He rang me out of the blue and said, ‘Do you fancy writing a book?’ I said, ‘On what?’ He said, ‘You tell me.’ I said, ‘Errr, well I’ve kind of had this idea of writing something about the North East, why we are the way we are.’ The term I love was coined by Bill Lancaster, who was briefly my supervisor at Northumbria, called ‘cultural archaeology.’ And I wanted to write something that takes that approach. That was in 2017. It took me about two years to get through the book. And I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the fact my mother was my research assistant; she wrote up all my notes. She was an old-school typist who could turn scribbles into text.”

***

“Did the people who live in this part of the world have different patterns of life, behaviour and attitudes? I think they did. Different expectations, different threats, different work. Were they different from the rest of England? I think there were. Did they call themselves Northumbrians to differentiate themselves from the rest of the country? No. How much were they aware of the rest of country? They had loyalty to their parish, to their local warlord, to the bishop, to Saint Cuthbert.”

The temptation to project modern sensibilities into the deep past – and search for a self-described, self-aware Northumbrian identity going back the centuries – is clearly a dead end. But questions about current identity, belonging and stereotype – and their origins – are worth asking. “The Geordie hard lad Jimmy Nail stuff is part of the North East, don’t get me wrong. Geordie Shore is part of it. I despise it yet I recognise that it’s a part of the region. Bear it down to the fundamentals: it’s bonny pit laddies and lassies drinking beers. Absolutely new-old masculinity. I think I touched on it in the book. The traditions of blokes getting dressed up in the North East is long, deep-seated, partly because they had disposable income to do it but partly because of the sociability culture of ‘gannin’ oot’ and enjoying yourself and catching the eye of people. And Geordie Shore fits very nicely into that.”

Many of the pleasures of Jackson’s book are seeing how the past and present fit together. How the “really boisterous laddish culture,” “the Stakhanovite thing in the North East of hard-work, totally obsessed with it as a matter of personal pride, which extended to women if not more so,” and the love of drink stem from historical precedents that have shaped the region. Indeed, historical hangovers still plague the current scene. “My theory is that you’ve got to understand that coal-mining and ship-building were some of the most interesting and heroic work that the British working classes ever did. Some people hated it and thought it was terrifying. Loads of people loved that work. They wrote songs about it. They missed it. My grandfather loved being a coalminer, adored it. Leaving aside all the camaraderie aspects of it, there was the thrill of it, the danger of it.

“But also, you’re sort of your own boss to a certain extent. You’re relying on your own craft and skill to tackle this problem. ‘We’ve got to get this coal out of here. How are we gonna do it?’ It’s not about brute force. It’s about intelligence and teamwork. Whereas working on a production line is alienating work. Where is your scope for self-expression and intelligence at Nissan? I may be doing them a disservice but all the intel I have received about working there is that they see it as a means to an end, a pay-check, they don’t see it as a way of life.

“And of course, it doesn’t support a way of life like the pit village did either where everyone was in it together. The wives supported their husbands and all that. It’s not just that the work isn’t as interesting. It doesn’t support that community that the coal mines and shipyards did. And we really haven’t got over that. The North East hasn’t got over this thing that they loved doing. That whole world is gone and we’re so not over it.”

This feeling of loss and profound change has been harmful to the North East’s sense of itself. Jackson’s The Northumbrians is in the end a call for unity between the region’s now opposing tribal identities. “I think the most damaging thing about the North East – and maybe I do have a political message – my one message, is we need to get our act together and speak with a collective voice. The Tyne-Wear rivalry is tedious. The tedious, tedious Tyne-Wear rivalry. I think it genuinely holds the region back like two bald men fighting over a comb as they said about the Falklands War. If this book had any political agenda it is to argue that we are fundamentally the same people.”

The Northumbrians: North-East England and its People is out now.

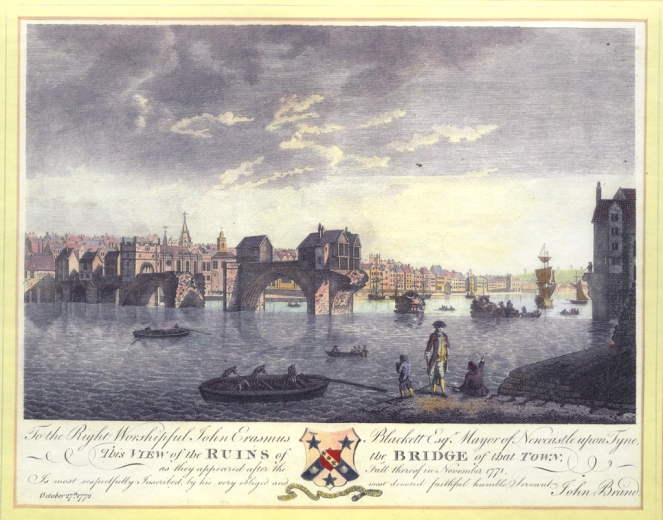

Photographs courtesy of Newcastle Libraries, Tyne and Wear Archives and Dan Jackson

Read my review of The Northumbrians in the LSE Review of Books

Interesting read, especially the bit about not having got over the past.

LikeLike